A rose by any other name still wants to be called Rose

One of the quickest ways to build bridges between you and another person is to know their name. Principals, central office administrators, and professors have many names to learn. School districts, large high schools, and big undergraduate lecture classes lead to a challenging volume of names. Wholehearted school leaders accept this challenge.

When we visit schools and classrooms, we don’t always know everyone’s names yet; this means we have to get to work straight away.

Baker/baker Paradox

The Baker/baker paradox suggests that if you meet someone and learn they are named Baker you’re not super likely to remember that. However, if you meet someone and learn they are a baker you are more likely to remember their profession. It is the same word associated with the same person; so why does this happen? This works because one (the profession) conjures an image while the other (the name) doesn’t.

You can use the Baker/baker paradox to your advantage by asking students to tell you something interesting about them as they tell you their name. Put the two bits of information together:

- Lorenzo speaks Spanish.

- Zoe likes photography.

- Kristen is a cheerleader.

- Joshua plays the piano.

- Rania is from Tunisia.

This has double advantages. First, it helps you learn names, and second, it gives you something to build on after you learn the person’s name.

Be Transparent

Let students know that their names matter to you because they matter to you. Tell students that it is hard to learn all of their names but that you are committed to working on it until you get it. And then be good to your word. When students see that I am invested in learning their names they help me with clues, laughter, and lots of encouragement. These are all wholehearted indicators of positive school culture.

As a school administrator, I visit a lot of classrooms, including classrooms at our partner schools around the world. Whenever I spend time in a new classroom, I share a little bit about myself and ask students to do the same. I let our students know that I want to get to know them and their names. Then I work really hard to do just that.

I spend a few minutes at the start of each lecture going around using the Baker/baker strategy trying to learn students’ names and an interesting fact about each of them. Later, if I can’t remember a student’s name, I apologize and ask them to remind me.

The Calculus Party Effect

In addition to bridging humanity, names also help with student engagement. Everyone lights up when they are recognized, affirmed, and named. The calculus party effect (known to everyone else as the cocktail party effect) refers to intense sensory situations (e.g. a calculus class). In these situations, amidst the flurry of approximating definite integrals and calculating arc length, we tend to shut out irrelevant information. However, we zoom back in when triggered by a highly-relevant phrase. What is the primary brain trigger for a highly-relevant phrase? Your name.

In a world where there are many calls on our attention, hearing your name brings you back to the present moment and refocuses your attention on the task at hand. This is an imperative strategy for teachers and school leaders.

Names Also Matter Online

As a blended school district, much of our correspondence is electronic. Our online teacher training includes meaningful lessons about humanizing online communication including always referring to students by name. In the online setting, you have to amplify your voice and compassion.

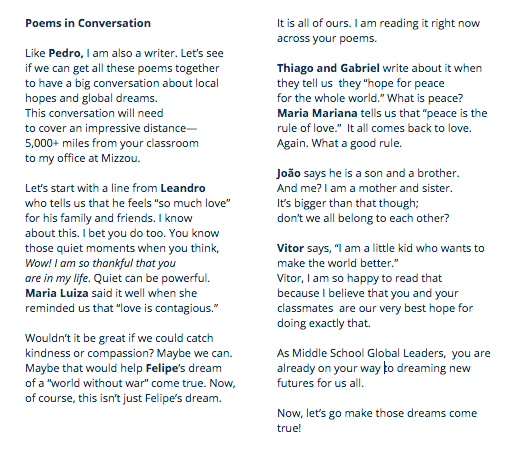

Recently I had the delight of receiving a collection of poems from a group of seventh-grade students in our Middle School Global Leaders program. The students are studying with us from Brazil and so, unfortunately, I couldn’t go around the hall and congratulate them. Instead, I responded with my own poem referring to each student in the project by name.

Pronunciation Matters Too

Because we are a global school district, some names are super difficult for my English speaking tongue. World Language Learner is a new term I am developing.

World Language Learner (Novice): Noun: A person who recognizes the importance of being culturally proficient in a multilingual world. While they are currently only fluent in one language they can say nice things, read emails, and order drinks in additional languages. This person is actively working on expanding their linguistic horizons using a variety of language learning apps often including Duolingo.

For novice World Langauge Learners, there are certain sounds that are hard to hear and even harder for us to pronounce. Don’t allow students to let you off easy by shortening their names or giving you a simpler nickname. Ask them to correct you and work with you until you get it right. Caring enough to learn names and get them right speaks volumes about your professionalism and humanity.

Sim, ainda estou trabalhando para pronunciar corretamente João.*

In conclusion, names matter or a rose by any other name still wants to be called Rose.

Appreciatively, Dr. KFW

* Yes, I am still working on correctly pronouncing the name João.

* “

* “